08 August 1915

SUVLA - Captain John Coleridge, Staff, 11th (Northern) Division, IX Corps - The morning of 8 August woke in silence at Suvla, with the exception of the occasional rifle shot high up on Kiretch Tepe. Elsewhere troops were milling around the beach area not knowing what to do. The Suvla landing was going astray, and crucial time was being wasted. The landing at Suvla was a surprise to the Turks, but it was now the time for IX Corps to take the advantage before the Turkish reinforcements would arrive.

Photograph: IX Corps men milling around near the shore at Suvla Bay.

Photograph: IX Corps men milling around near the shore at Suvla Bay.

Coleridge, a 11th Division staff officer, was sent out early on the 8 August by Divisional HQ to make a general reconnaissance to ascertain the troops positions and impress the importance of gaining the W Hills before nightfall. This report gives a very good indication of the situation and the state of the men:

"I left D.H.Q. about 9 a.m. and walked towards Chocolate Hill. En route I passed the line of trenches dug from the Salt Lake to the sea, and found the 6th Lincolns and 6th Borders coming into them, having been relieved north of Chocolate Hill by the 7th South Staffords. The men were quite cheerful, and I was told that the Brigadier (Maxwell) had gone to Chocolate Hill. On arriving there I found the place crammed with men, both 31st and 33rd Brigades. The men were tired and thirsty, but not depressed, and there was plenty of bully and biscuits to eat. I met Generals Maxwell and Hill, and we went to Hill 50 [Green Hill] together. The enemy was very quiet, just a casual bullet now and then. The Brigadiers both agreed that there were very few Turks on W. Hill, and that the men, given a few hours rest and some water, could well go on and attack W. Hill. I warned them to expect orders. I then went northward, and saw the South Staffords. The troops were in good order. They had, I think, got a little water from Ali Bey Cheshme. I believe, but will not swear to it, that the South Stafford were already on Hill 70, anyhow they were good fighting value. I then turned rather more westwards, and crossed the scene of the previous day’s fighting. There were a few corpses and some equipment lying about (not in excess), but most of the dead had been buried. I then came to the 6th Yorks. The battalion only had five officers with it, and the men were distinctly demoralised. In my opinion the battalion wanted relief. I then visited the West Ridings, York and Lancaster (practically untouched) and the West Yorks. I stayed with them some time and watched the Dorsets have a set-to with some Turks and progress slightly. I did not see the Manchesters. I then went to Hill 10, and saw Colonel Minogue and Shuttleworth. They were both confident they could get on when ordered, provided they were not asked to cover too wide a front and that the troops from Chocolate Hill moved forward simultaneously. They agreed with me that the 6th Yorks were of no fighting value. I then went towards the Beach and saw the two Fusilier battalions, both somewhat shaken, especially the Lancashire Fusiliers. I did not see the Brigadier (Sitwell)."

Aspinall, sent ashore by Sir Ian Hamilton to find out what was happening, sent the following message to GHQ:

"Just been ashore, where I found all quiet. No rifle fire, no artillery fire, and apparently no Turks. IX Corps resting. Feel confident that golden opportunities are being lost and look upon the situation as serious."

Due to lack of communication from General Stopford, Hamilton went to Suvla to find out for himself the situation. Hamilton was furious after hearing excuses from Stopford and demanded action. Stopford’s IX Corps had twenty two battalions at Suvla against approximately three Turkish battalions, so now was the time to strike and build on the surprise of the landing. Hamilton wanted the high ground known as Tekke Tepe taken immediately. Once captured it was hoped that Suvla Bay would be secure and attention could be given to the desperate situation that was developing at Anzac.

SOURCE: Coleridge, J.D., quoted in Major Dudley Ward, History of the 53rd Welsh Division (Cardiff: Western Mail, 1927), p.23.

Aspinall-Oglander, Brig-Gen C.F., Military Operations Gallipoli, Vol.I., (London: Heinemann, 1929).

HELLES - Accounts from Captain William Forshaw, Sergeant Harry Grantham, Lance Corporal Thomas Pickford and Lance Corporal Samuel Bayley, 1/9th Manchester Regiment, 127th Brigade, 42nd Division - A second diversionary attack by the 42nd Division made on 7 August was soon thrown back by the Turks and the only gain left was in the Vineyard sector. Here some of the worst fighting was experienced by the 1/9th Manchesters when they moved up to relieve the Lancashires. A key figure in the defence of the north-west corner of the Vineyard on 8 August was Captain William Forshaw.

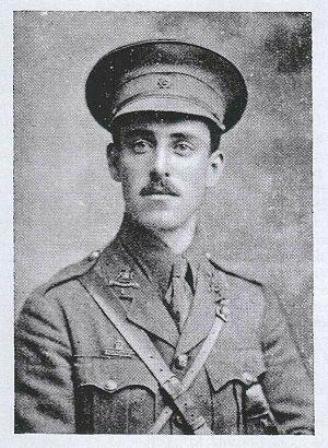

Photograph: Captain William Forshaw VC

Photograph: Captain William Forshaw VC

"I and about twenty men were instructed to hold a barricade at the head of the sap. Facing us were three converging saps held by the Turks, who were making desperate efforts to retake this barricaded corner, and so cut off all the other men in the trench. The Turks attacked at frequent intervals along the three saps from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning, and they advanced into the open with the objective of storming the parapet. They were met by a combination of bombing and rifle fire, but the bomb was chief weapon used both by the Turks and ourselves."

Alongside Captain Forshaw at the head of the sap was Sergeant Harry Grantham.

"There were all sorts of bombs. Round bombs and bombs made out of jam tins and filled with explosives and bits of iron, lead, needles, etc. It was lively while it lasted. We could see the Turks coming on at us, great big fellows they were, and we dropped our bombs right amidst them. Captain Forshaw was at the end of the trench. He fairly revelled in it. He kept joking and cheering us on, and was smoking cigarettes all the while. He used his cigarettes to light the fuses of the bombs, instead of striking matches. “Keep it up, boys!” he kept saying. We did, although a lot of our lads were killed and injured by the Turkish firebombs. It was exciting, I can tell you."

The bombs used by both sides lacked a genuine lethal potency, they could of course kill, but not having a great deal of explosive power or a proper fragmentation casing they were far more likely to wound, or bespatter the victims with cuts from the hundreds of minute fragments. That is not to say that they were not dangerous if you were unlucky or over-ambitious as was discovered by Lance Corporal Thomas Pickford.

"Bombs were bursting all around us. Some of the boys in their excitement caught the Turkish bombs before they exploded, and hurled them back again. They did not always manage to catch them in time and three of them had their hands blown off. What made the position worse was that as soon as we had entered the trench a bomb laid out six of us. I was one of them. I bandaged up my leg, bandaged the others and sent them back - I carried on."

The fighting continued for the best part of two days. Even when the 1/9th Manchesters were relieved, Forshaw insisted in staying on to lead the defence.

"I was far too busy to think of myself or to think of anything. We just went at it without a pause while the Turks were attacking, and in the slack intervals I put more fuses into bombs. I cannot imagine how I escaped with only a bruise from a piece of shrapnel. It was miraculous. The attacks were very fierce at times, but only once did the Turks succeed in getting right up to the parapet. Three attempted to climb over, but I shot them with my revolver. All this time both our bomb throwing and shooting had been very effective, and many Turkish dead were in front of the parapet and in the saps. The attack was not continuous, of course, but we had to be on the watch all the time, and so it was impossible to get any sleep. Fortunately, we had no fewer than 800 of those bombs, but we got rid of the lot during the greatest weekend I have ever spent."

The physical and nervous exhaustion that followed in the aftermath of their eventual relief took a toll on Forshaw, despite his apparent insouciance as Lance Corporal Samuel Bayley noticed.

"Myself, a few men and the Captain held a trench which was almost impossible to hold, but we stuck it like glue, in spite of the Turks attacking us with bombs. I can tell you I accounted for a few Turks. Our Captain has been recommended for the V.C. and I hope he gets it because he was very determined to hold the trench till the last man was finished. But we did not lose many. Our Captain has not got over it yet, but it is only his nerves that are shattered a bit."

Forshaw would be awarded the VC for his reckless disregard for his personal health (Smoking kills!) and would forever be known as the ‘Cigarette VC’. The fighting over the Vineyard - an area of grounds just 200 yards long and 100 yards wide - continued for several days as the British strove to incorporate it into their lines and the Turks tried to eject them.

SOURCES:

INTERNET SOURCE: W. T. Forshaw quoted in Ashton Reporter, 16/10/1915 http://ashtonpals.webs.com/

INTERNET SOURCE: H. Grantham quoted in Ashton Reporter, 16/10/1915 http://ashtonpals.webs.com/

INTERNET SOURCE: T. Pickford quoted in Ashton Reporter, 18/3/1916 http://ashtonpals.webs.com/

INTERNET SOURCE: S. Bayley quoted in Ashton Reporter, 11/9/1915 http://ashtonpals.webs.com/

Photograph: Lieutenant Colonel William Malone

Photograph: Lieutenant Colonel William Malone

ANZAC - Major General Frederick Shaw, Headquarters, 13th Division and Major William Cunningham, Wellington Battalion, New Zealand Brigade, NZ&A Division - As part of a general advance the Wellington Battalion supported by the 7th Glosters and 8th Welch Regiment were to spearhead a renewed attack on Chunuk Bair after an artillery bombardment and massed machine gun fire commencing at 03.30. To general surprise this seems to have caused the Turks to temporarily withdraw from the summit. The 13th Division commander, Major General Frederick Shaw, was watching the attack.

"There is an observation post here and from it one can see a large portion of the country over which we are operating. To that post about 4.15 went a procession of sleepy Generals and staff carrying glasses, telescopes and anxiously awaiting the dawn, to show the success or otherwise of the troops. It began to get gradually lighter and all glasses were turned on the summit of Chunuk Bair, which was the only point of attack which could matter. Still it got lighter, and then someone said "I see men on Chunuk Bair", "They are our men", said another, and then "By Jove! They are our men", and so they were. We reached the summit, should we hold it and should we progress?"

Major William Cunningham of the Wellington Battalion takes up the story.

"Each Company was approximately 200 strong and this solid phalanx of men emerged from the Apex just before the shelling ceased. It was expected that stiff opposition would be met with at the top. The orders were that immediately the ground permitted, Companies were to open out to a frontage of 100 yards each and to fix bayonets, but to keep well closed up; that no shot was to be fired, but the position was to be carried with the cold steel. Some distance had to be traversed before the leading platoons were able to open out at all and it was less than 150 yards from the top of Chunuk Bair, where bayonets were fixed on the move. The two leading companies swept in line in a final rush to the top, to find to their amazement the position was unoccupied. Certainly a small Turkish piquet was overwhelmed, without firing a shot, in a small trench on the seaward slope some distance from the top. But where were the Turks who had shattered the Auckland attack?"

Still the Wellingtons were hardly complaining and they began to try and consolidate their positions. Behind them the 7th Gloucestershires and 8th Welch Regiment suffered far more as they were exposed to a deadly enfilade fire in reaching the summit where the remnants took up positions on the flanks of the Wellingtons. Malone split his companies between the forward and reverse slopes of Chunuk Bair, but they soon encountered serious problems as is recounted by Major William Cunningham.

"For the best part of an hour the Wellington Battalion was unmolested in its digging operations, but owing to the hard and stony nature of the soil, and the fact that the majority of the men had only entrenching tools, progress was very slow, and the trenches were not more than 2 feet deep when the Turkish counter-attack started. Preceded by showers of bombs, the Turks worked their way up until they were able to fire into the gun-pits where our advanced covering parties had been placed. These pits soon became untenable and the survivors of the covering parties returned to their companies in the new front line. By now all digging had ceased and the front line companies, taking what cover their shallow trench line afforded, were engaged in a deadly musketry duel with the Turks, who were crowding up from the valley to recapture the hill. Enfilade machine gun fire from the old Anzac position made matters most unpleasant and soon the shallow front line trenches were filled with the killed and wounded. No longer able to hold the forward line, a few unwounded men were able to dash in safety to the reverse or seaward slope of the hill."

That retreat left the Turks able to creep forward, leaving the Wellingtons only able to cling to their shallow trenches on the reverse slope and losing control of the brow of the hill. Some meagre reinforcements arrived but never as many as were replenishing the Turkish ranks. Here again is Cunningham's account.

"Odd Turks began to work into a position from which they could fire into the reverse slope of the hill. When the forward trenches had been abandoned the Turks crept up close enough to the crest line to hurl showers of egg bombs among the men on the reverse slope. These had long fuses and were promptly thrown back before they exploded. Bolder and bolder, the Turks essayed a bayonet charge, but were promptly stopped by a few well directed volleys at point-blank range. Several times the Turks gallantly repeated their attempts to charge over the top, but always with the same result. Ammunition was running short, and had to be collected from the dead and wounded. As the day wore on, still the defenders of the hill stuck stubbornly to their ground. In the afternoon a Turkish battery searched the slopes where our men were with accurately timed shrapnel. This shelling ceased about 4pm, but Colonel Malone fell a victim to the last salvo. He stood up in the trench where his headquarters were thinking the shelling had ceased and practically the last round fired killed him instantly."

William Malone, one of the most endearingly grumpy, yet supremely efficient, characters of our Gallipoli Day by Day series was dead. He would never see his beloved wife again.

The shattered remnants of the Wellingtons, (just 70 unwounded were left of the 760 who had originally occupied the crest) 7th Gloucestershires and 8th Welch were relieved after dark on the night of the 8 August by the Otago Battalion and the Wellington Mounted Rifles. With more Turkish divisions marching purposefully towards the Sari Bair heights the chances of such exposed positions being held were minimal.

"SOURCE:

IWM DOCS, F. Shaw, diary, 8/8/1915, W. H. Cunningham, Chunuk Bair Attack: New Zealand Infantry Brigade (Reveille, 1/8/1932), p.87