28 April 1915

HELLES - FIRST BATTLE OF KRITHIA - With the Helles beachheads now consolidated, the weary and battered troops of the 29th Division could now make their final advance on Krithia, with plan to seize Achi Baba and then carry the Kilid Bahr Plateau further on. Around the beaches there was much congestion from the continuing landings of further troops, ammunition, stores, food and water. The men at this stage were becoming extremely fatigued from prolonged exertion and a lack of sleep that they had endured over the past couple of days.

Fighting their way onto the beaches, repelling heavy Turkish counter-attacks, digging trenches, building encampments and bringing up supplies had begun to take their toll. The Turks, retiring back to Achi Baba, were in a similar situation, equally exhausted and in disarray. During the brilliant sunlight of the afternoon the general allied advance met with little resistance. As dusk fell, the allies had safely secured the toe of the Peninsula to a depth of about two miles, halting as night set in. This gave the troops some sense of further achievement, although the situation for the allies was still critical.

Fighting their way onto the beaches, repelling heavy Turkish counter-attacks, digging trenches, building encampments and bringing up supplies had begun to take their toll. The Turks, retiring back to Achi Baba, were in a similar situation, equally exhausted and in disarray. During the brilliant sunlight of the afternoon the general allied advance met with little resistance. As dusk fell, the allies had safely secured the toe of the Peninsula to a depth of about two miles, halting as night set in. This gave the troops some sense of further achievement, although the situation for the allies was still critical.

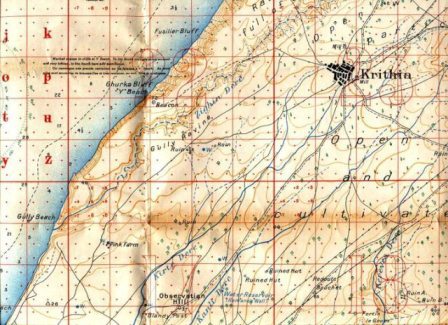

At 08:00, 28 April, the First Battle of Krithia began with a fairly meagre bombardment. The 29th Division attacked on the left, while the recently landed French 1st Division attacked on the right flank. Coming up against little Turkish resistance at first, mainly isolated snipers and the occasional shrapnel burst, they very soon met with more determined opposition from entrenched Turkish positions. 87 Brigade advanced on the left, their objective being Sari Tepe on the Aegean coast, and Yazy Tepe (Hill 472) at the end of Gully Ravine. 88 Brigade, in the middle, were to capture Krithia itself, whilst the French, on the right, were to link up at Kanli Dere with the British. This optimistic advance of over five miles was to be made by tired troops, using a complicated wheeling movement, against an unknown terrain and unknown enemy positions and with little artillery support. It was a recipe for failure.

1st Border Regiment and 1st Inniskilling Fusiliers were the first British troops to reach the southern area of Gully Ravine, securing its mouth and Gully Beach with no resistance. The advance continued astride the ravine, with the Borders advancing along the bare strip of rocky ground that became known as Gully Spur, and the Inniskillings on the eastern side of the ravine along what became known as Fir Tree Spur. But by mid-day, this hopelessly organised advance had lost its earlier momentum. A Turkish strongpoint, near the abandoned Y Beach, began firing, which was enough to bring the advance along both spurs to a standstill. These dead-tired invaders needed no other excuse. In no fit state to carry out an attack in the first place, many just collapsed, utterly exhausted.

Very few artillery pieces had been landed at this stage, and those that were, only offered desultory support, and in many cases had to fire blind into the unknown enemy positions. The navy did fill this gap, and offered critical support to the land forces during these early days. Off Y Beach, HMS Queen Elizabeth helped save the day in support of the tired Border Regiment who at one stage broke in the face of a Turkish counter attack. In Midshipman G. M. D. Maltby’s journal he described the Turkish counter attack on Gully Spur:

“We weighed at 10.15 and steamed to “Y” beach, opening fire almost immediately with our 6” (guns) on Turks in trenches amongst scrub. At 1.30 our 15” opened fire with shrapnel at difference parts of cliff to left of Y beach ceasing fire 6 minutes later. At 12.30 the Huns [sic] could be distinctly seen rapidly advancing and firing from behind the farthest ridge. They came along in huge numbers, and there being only a few of our men in the advance trench to meet them. These fellers became demoralized and many ran over the cliff, but the situation was partially saved by our 15” (13,000 bullets), which exploded bang over the Huns and those that it did not flatten out turned. These were wiped out by a salvo of our 6” shrapnel." (Midshipman GMD Maltby, HMS Queen Elizabeth).

ANZAC - Our first New Zealand perspective of the fighting at Anzac. Colonel William Malone was a gruff old civilian-soldier born in 1859 and with little tolerance for those he that did not match his own high standards in every respect. He had a bias against Australians that he rarely failed to express with his habitual bluntness.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone, Wellington Battalion, New Zealand Brigade, NZ&A Division, NZEF

Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone, Wellington Battalion, New Zealand Brigade, NZ&A Division, NZEF

"There is no question but that the New Zealander is a long, long way the better soldier of the two. The Australian, is a dashing chap, but he is not steadfast, and he will not or would not dig, work. He came here to kill Turks, not to dig, and consequently, we have suffered. There are lots of good men and good officers among them, but they are not disciplined or trained like our men. The New Zealander is a long way the better soldier, more steadfast, better disciplined and a worker. I don't like the average Australian a bit, in fact I dislike him!"

In the extremely stressful conditions that existed in the Wellingtons positions up on Walkers Ridge on 28 April it is not surprising that Malone thought and said things that a more mature reflection or armchair analysis might find abhorrent.

"We are well dug in. The Turks keep trying to blast us away and thro the day killed three or four and rounded eight or nine The ground is covered with scrub. We go on digging and are shelled and rifle fired at night and day, but thanks to our excellent digging our casualties get less. I insisted on the Australians being all withdrawn. General Walker asked if I could hold on without them. I told him they were a source of weakness. All last night they kept up a blaze of rifle fire, into the dark at the Turks who they could not see and thus drew fire. The Turks knowing where we were. I tried to stop them but it was useless. About lam Colonel Braund came to me for more ammunition. I refused to give it to him telling him he was wasting enough and only informing the Turks that he was scared. He insisted and said responsibility on me. I sat tight and told him to go see General Walker as without his order I absolutely refused to give him any more ammunition. At 6am the Australians left. It was an enormous relief to see the last of them. I believe they are spasmodically brave and probably the best of them had been killed or wounded. They have been I venture to think badly handled and trained - officers in most cases no good. I am thinking of asking for a Court Martial on Colonel Braund. It makes me mad when I think of my grand men being sacrificed by his incapacity and folly. He is I believe a brave chap because he did not keep out of the racket. If he had it would have been better for us."

It is worth noticing that many other people admired the performance of Lieutenant Colonel George Braund (an Australian Member of Parliament who had raised and then commanded the 2nd Australian Battalion) who had helped hold the exposed positions up on Russell's Top and the Nek above Walkers Ridge..

SOURCE:

Diary of GMD Maltby, private collection (S. Chambers), W. G. Malone quoted J. Crawford, "No Better Death: The Great War Diaries and Letters of William G Malone" (Auckland: Reed Publishing Ltd, 2005), p.167 This is an excellent book and in my view should be in everyone's Gallipoli library. The photo shows the Wellingtons digging in on Walkers Ridge. It is from the Malone Family Collection and was is reproduced from p.166 of No Better Death